This post is also available in:

Español

Español

Many people mistakenly believe that the origins of Bomba and the origins of Plena are the same, or at least similar. But that is not the case.

I’ll give you one quick fact that addresses this myth. Bomba originated around the 17th century, but it truly developed to the form we know today around the 19th century.

Plena was created in the 20th century. The only thing that ties them together is that both are folkloric rhythms created by blacks based on drum beats. Because of their percussive backgrounds and their folkloric denomination, musical groups that play one genre also tend to play the other as well, although this is not always necessarily true.

Since it would take an encyclopedic volume to discuss all the details regarding the origins of Bomba, I’ll just highlight the main events in this blog.

Slavery in Puerto Rico

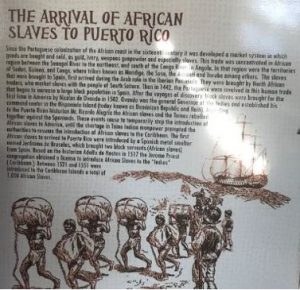

The Spaniards began bringing African slaves into Puerto Rico (named San Juan Bautista back then) in the early 16th century. They introduced about 1,050 slaves into the Caribbean between 1521 and 1551.

Since the Taino Indians didn’t prove durable enough for hard labor, the African slaves were used in the sugar cane plantations around the coastal plains of the island. The Africans inevitably began building drums in order to play the music they used to play back in Africa.

With the passing years and centuries, the music evolved. New rhythms were created.

It so happens that some historians claim that the origins of Bomba can be traced as far back as the late 16th century. However, the rhythm of Bomba closest to its current form started sometime in the first quarter of the 19th century.

The Structure of Bomba

I found a great article that captures, in what I believe is the right degree of detail, the structure of Bomba. I’ve extracted this from “A Challenge for Puerto Rican Music; How to Build a Soberao for Bomba” by Halbert Barton.

“While the historical and regional continuities are complex, there are a few constants which most can agree on, such as that any Bomba tradition worthy of the name must include the following:

CALL-AND-RESPONSE SINGING:

Mostly in Spanish, but some in Afro-French Kreyol and some in Congolese; sometimes with an opening litany (as in some songs from Mayagüez, e.g. “Sepulate” by Don Félix Alduén); the refrains that are repeated tend to be rather short and suggestive and have a percussive, chant-like quality, often using simple melodies on a pentatonic scale and may, or may not, include vocal harmonizing.

POLIRHYTHMIC DRUMMING:

In variants of 2/4, 4/4, 6/8, and 12/8, with interlocking and multilayered rhythms formed by the three-part basic instrumentation and the percussive call-and-response vocal ensemble.

THREE-PART BASIC INSTRUMENTATION:

(1) at least two goat-skin barrel drums, including at least one Buleador (low drum), which repeats a rhythmic phrase, and one Subidor or Primo (high drum), which improvises on top of, and in conversation with, the basic rhythm played by the Buleador; the Subidor is also used to sonically interpret a solo dancer’s movements.

(2) one Cuá, or stick drum, using two sticks on a hollow bamboo log or on the side of a drum, usually playing a pattern that corresponds to the basic rhythm of the Buleador.

(3) one large gourd Maraca.

DANCE STEPS:

(1) distinct paseo, or promenade, steps that correspond to the basic rhythm being played; for dancing in pairs or groups or chorus line, without calling for beats from the Subidor.

(2) piquetes, improvised steps and gestures that call for beats to be precisely marked by the Subidor.

(3) all dance steps, whether improvised or codified by rhythm, must display the basic values of good posture, elegance, and firmness (three values somewhat open to interpretation and in the eyes of the beholder, and thus open to controversy).

THE DRUM-DANCE CHALLENGE OR RETO:

At virtually any moment in a Bomba dance event, a solo dancer may break off from the rest of the group or ensemble and approach the Subidor to begin doing piquetes, improvised steps that call for particular beats and sound combinations to be marked on the drum by the Subidor.

The challenge for the drummer is to mark these steps by reading the body language of the dancer without knowing what the dancer is going to do in advance. The challenge for the dancer in this “agonistic dialogue” is to get and hold the drummer’s attention and increase the challenge by executing steps that progressively increase the overall energy and vitality of the musical ensemble, and then end the challenge at the highest peak of intensity, reverting to the basic step”.

I doubt that there’s a better description of Bomba than the above one by Barton. That’s why I decided to not even try to summarize or paraphrase it.

Here’s a video of “Sepulate” referenced above by Barton as a Congolese creole language song.

Bomba: Music for Dancing

The rhythm of Bomba was made primarily for dancing. There are mentions that it was used by the slaves in Puerto Rico as a way to protest or voice their disgust. This theory was recently repeated in an article published by the New York Times.

Although I guess it’s possible that there may have been a case or two of Bombas for this purpose (I’ve yet to find an example of such), the structure of Bomba is clearly not for that purpose.

As Burton wrote, “…the refrains that are repeated tend to be rather short and suggestive… often using simple melodies…”

When you listen to any Bomba, you can tell that the lyrics are “short” and “simple”. They are not built to tell stories or voice protests like is commonly done with Plenas.

As illustrated in the video above, the “piquete“, as a challenge to the Subidor drummer, is the main characteristic of the Bomba dance.

Here’s another video where it highlights the “piquete“.

Types of Bomba: Prelude to Part 3 and Part 4

So far we covered the origins and structure of Bomba. The next topic will be on the various types of Bomba that we have.

In Part 3 of this series, we’ll go into WHY we have various types of Bomba. Then in Part 4, we’ll talk of each one of the types of Bomba in detail.

I hope you’re finding this series

[…] Part 2 of this series, I mentioned two of the three differences between Bomba and […]

bomba