This post is also available in:

Español

Español

In the mid 1970’s when the Salsa boom was at its peak in New York, brothers Andy and Jerry Gonzalez decided to form a group to experiment with the folkloric roots of Salsa.

But the reason to do it might surprise you.

Origins of Grupo Folklorico y Experimental Nuevayorkino

Salsa music in the 70’s was thick and heavy. Many of us reminisce that music for it’s creativity and the concept of the whole band chipping into the musical experience, not just the singers.

Jerry and Andy weren’t having it.

By then, Fania Records had become a well-oiled machine of producing Salsa hits. But as writer Juan Flores and musician/producer René Lopez pointed out in their article “Salsa Memory: Revisiting Grupo Folklórico y Experimental Nuevayorquino”; “by the mid-1970’s [Salsa music was] already degenerating into a formulaic commodity field characterized by a predictable and overproduced sound.”

It could be hard for some to comprehend that last statement because the music produced during the Salsa Romantica era and afterward doubled-down on that formulaic and “overproduced” sound. It basically muted any musician creativity that might have survived the Fania-era productions, to instead highlight solely the singer.

Salsa songs became like pancake mix; just add lyrics.

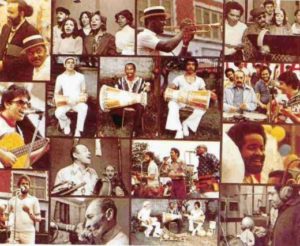

As word spread of the Gonzalez brothers’ plan, the group became a magnet that attracted New York’s best “rumberos“, and other musical rebels of the time.

In 1974, Andy and Jerry Gonzalez formally named it the Conjunto Anabacoa, and by 1975 they recorded their first of two albums, “Concepts in Unity”. By then René Lopez had convinced the brothers to rename the group to something much more descriptive of their music; Grupo Folklorico y Experimental Nuevayorkino. BTW, the second and last album, “Lo Dice Todo“, would come a year later.

The Music of Grupo Folklorico y Experimental

Here’s how Juan Flores describes the music of Grupo Folklorico y Experimental:

“Grupo’s guiding aesthetic of folkloric tradition and contemporary experimentation rooted in a specific social place—Nueva York—aimed to offer a clear, attractive, and real alternative to the deracinated, decontextualized, and creatively stifling results of the commercializing process.

The key term for this kind of music making is “descarga”, the jam session. It is informal, improvisational, and fun, as a matter of principle. Originally, “descargas” often happened in after-hours clubs and private parties…and without any scored arrangements whatsoever or even much by way of a preconceived plan.

As for the music itself, the taproot and trunk of the stylistic tree is of course Afro-Cuban music in its wealth of variants, especially the rumba guaguancó–son montuno continuum. But the albums contain many other genres, most of them brought into lively interaction with that basic stylistic modality: guaracha, bolero, charanga, Puerto Rican bomba and plena, Brazilian samba and bossa nova, calypso, Mozambique, and of course various jazz idioms are all present in this constantly shifting and surprising pastiche. There is not a piece in either of the collections that is not in the tradition of one or the other “folkloric” form, yet there is also none in which this primary style is left intact, as it were, and not interrupted and mixed with other stylistic languages.”

The Musicians

Once again I’m going to draw from “Salsa Memory” as Juan Flores describes very lyrically the musicians that came together for the Grupo Folklorico y Experimental.

“Drawing together a dream team of practitioners from a range of Afro-Cuban and Puerto Rican genres, arguably the best at their respective instruments, the formation of Grupo was obviously not at odds with the “allstar” idea. What was different about Grupo and what set it in polar contrast with the Fania enterprise and the salsa-as-Fania narrative were its musical concept, practice, and product.

To start with the personnel and instruments, the original group’s forte and binding element was of course the rhythm section, anchored in Manny Oquendo’s solid timbales, Andy González’s versatile bass, Oscar Hernández’s percussive piano, and an array of seasoned drummers including Milton Cardona, Frankie Rodríguez, and Gene Golden on batás and Jerry González on tumbadora and quinto. Other instrumental mainstays included the masters Chocolate Armenteros on trumpet, Nelson González on tres, Jose Rodrigues and Reinaldo Jorge on trombone, and flutist and tenor saxophonist Gonzalo Fernández. The main vocalists were the seasoned Cuban Virgilio Martí; Willie García, already a veteran Cuban salsa singer at the age of thirty-six; and street musician par excellence Genaro “Henny” Alvarez, a Puerto Rican drummer, composer, and singer.

This core of accomplished and highly regarded exponents of Cuban and Afro-Caribbean music, plus an assortment of special guest appearances and cameos by the likes of master batá drummer and singer Julito Collazo, violinist Alfredo de la Fé, legendary vocalist and composer Marcelino Guerra, and Carlos “Caito” Díaz, who had been a vocalist with La Sonora Matancera since its founding in 1924, assured a seemingly boundless resource of musical possibilities and experiments in multiple musical languages.

Though they were all stars or were to become stars in subsequent years, the idea was not so much a lineup of celebrities as a collective of players in synch, held together by their love for the music, respect for each other, and connection to community and by the guiding premise as conceived primarily by the González brothers (Andy and Jerry) and Manny Oquendo and by the steady-handed and expert sensibility of producer/mastermind René López.”

Legacy of Jerry Gonzalez

The Grupo Folklorico y Experimental Nuevayorkino only recorded two albums. After that, the members began re-taking some of their own projects.

The closest thing to a follow-up to the Grupo’s concept was Manny Oquendo’s Conjunto Libre, which casted Andy and Jerry Gonzalez, as well as Oscar Hernandez and Nelson Gonzalez. Dave Valentin and Papo Vazquez also joined the group in flute and trombone respectively.

After that, the ramification of the experimentation continued with Jerry Gonzalez and his Fort Apache band, Papo Vazquez and his Pirate Troubadours, and Oscar Hernandez, who after several years with Ruben Blades’ Seis del Solar, went on to form the Spanish Harlem Orchestra.

Jerry moved to Spain and continued to experiment with music beyond the Fort Apache. His love for music constantly pushed him in the direction of experimenting with the descarga concept applied to folkloric rhythms mixed with jazz elements. Be that guaguanco, bomba, plena or flamenco, Jerry’s experiments and body of work left a legacy of music, but perhaps more importantly, he also left the legacy of a creative concept for making music.

Note: I highly recommend you check out the full article written by Juan Flores and René Lopez, “Salsa Memory: Revisiting Grupo Folklórico y Experimental Nuevayorquino”